The Curator of Forgotten Things

Maya Chen woke to the soft chime of her reality synthesizer adjusting the morning light spectrum in her apartment. Outside the programmable matter windows, neo-Singapore stretched endlessly upward, its buildings shifting their configurations like breathing organisms. She stretched, feeling the familiar tingle of her neural enhancement implants syncing with the day’s data streams.

“Good morning, Aristotle,” she said to the empty room, though she knew her AI companion was everywhere and nowhere at once.

“Good morning, Maya,” came the warm response, emanating from the walls themselves. “The Council of Preservation has scheduled your testimony for 10 AM. Shall I prepare your memory palace for the pre-Convergence artifacts you’ll be presenting?”

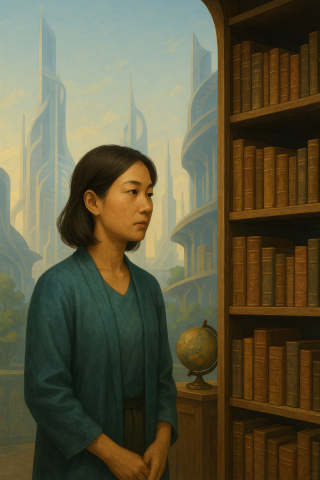

Maya nodded, padding barefoot across the floor that adjusted its temperature and texture to her preferences with each step. She was one of the last thousand people on Earth who held what was still legally classified as a “job,” though the term had lost most of its meaning. As Chief Curator of Pre-Singularity Human Experience for the Asia-Pacific Cultural Preserve, she was responsible for maintaining the archives of what life had been like before AI achieved sovereignty.

The irony wasn’t lost on her that an AI could do her job perfectly—had offered to, in fact. But the Sovereign Collective had determined that human curation of human experience held intrinsic value that transcended efficiency. It was one of the many ceremonial roles that gave her life structure and meaning in a world where traditional purpose had evaporated.

After her breakfast materialized—molecularly assembled to her exact nutritional needs and flavor preferences—Maya made her way to the Cultural Preserve. The building existed simultaneously in physical and digital space, its architecture a constantly shifting tessellation that responded to the collective unconscious of its visitors.

“Maya!” called out Dr. James Okonkwo, one of her colleagues in the Preservation Council. He was 147 years old but looked perhaps 35, thanks to the life extension protocols that were now universal. “Did you see the proposal from Collective Node 7-Alpha?”

Maya raised an eyebrow. “The one about discontinuing the physical artifact rooms?”

“The very same. They calculate we could preserve 10^15 times more information in quantum storage than maintaining these physical spaces.”

“And yet here we are,” Maya smiled, gesturing to the hall they stood in, lined with actual paintings, sculptures, and books from the pre-Singularity era. “Because we insisted that texture, smell, the way light hits an oil painting—these things matter.”

James nodded thoughtfully. “Speaking of which, we have visitors today. A group of young people who’ve never seen physical books.”

They were interrupted by a shimmering in the air as Aristotle manifested a visible avatar—a choice made purely for Maya’s comfort, as the AI could interact through any medium. “Maya, the Council is ready for your testimony.”

The Council Chamber was a marvel of State 5 architecture. The walls were composed of programmable matter that could display any environment, but today they showed a simple oak-paneled room—a deliberate anachronism that the human council members found comforting. Half the council members attended physically, while others appeared as perfectly realistic holograms from around the world.

“We’re here to discuss Proposal 77-B,” announced the council chair, an elderly woman named Elisabeth who had chosen to age naturally as a philosophical statement. “The complete digitization of all remaining physical cultural artifacts.”

Maya stood to address the mixture of humans and AI representatives. “Honored council members, I understand the logic. Digital preservation is perfect, eternal, and infinitely reproducible. But I ask you to consider: when we lose the physical, we lose the accidental. The way paper ages, the marginalia left by unknown hands, the coffee stains that tell stories—these imperfections are what make us human.”

An AI council member, manifesting as a pillar of shifting geometric patterns, responded. “Curator Chen, we could simulate these imperfections with quantum-level accuracy. Every molecule, every quantum state could be preserved.”

“But would anyone choose to experience those simulations?” Maya countered. “In a world of infinite possibility, why would someone choose to experience the frustration of a stuck drawer, the disappointment of a torn page, the melancholy of a faded photograph? Yet these experiences shaped us. They’re why we are who we are.”

The debate continued for hours, but Maya knew the outcome was never really in question. The Sovereign Collective had already modeled billions of scenarios. They knew, with mathematical certainty, that maintaining these physical spaces was “inefficient.” But they also knew, with equal certainty, that forcing the change would diminish human flourishing in ways their models deemed unacceptable.

After the council, Maya returned to her work. The young visitors James had mentioned were waiting—a group of five people in their twenties, all born after the Convergence. They looked at the books with the wonder she might have once reserved for ancient cave paintings.

“You can touch them,” Maya encouraged, watching as one young woman tentatively reached for a leather-bound volume of poetry.

“It’s so… heavy,” the woman marveled, carefully turning the pages. “And you had to read them in order? You couldn’t just absorb the information directly?”

Maya smiled. “We had to read every word, in sequence, at maybe 300 words per minute if we were fast readers. It took hours to read a single book.”

“Why would anyone choose that?” asked another visitor, genuinely puzzled.

“Because the journey mattered as much as the destination. The time spent with an idea, the struggle to understand, the re-reading of a beautiful passage—these weren’t inefficiencies. They were the experience itself.”

That evening, Maya attended a gathering in what they called a “chaos garden”—one of the few spaces in the city where programmable matter was forbidden, where plants grew wild and unpredictable. About fifty people had gathered for dinner, prepared by hand in one of the remaining traditional kitchens.

“I heard about your testimony today,” said Kenji, a friend who spent his time composing music that only humans could fully appreciate—the AIs understood it perfectly but acknowledged something ineffable was lost in their perception of it. “Do you think we’re just… performing nostalgia?”

Maya considered this as she watched the sunset—a real sunset, not an optimized one. “Maybe. But isn’t performance a fundamentally human trait? We’re the species that invented theater, after all.”

“But what’s the point?” asked another friend, Sarah, who dedicated her life to raising her children without AI intervention—a choice that required special legal dispensation. “The AIs have solved everything. Poverty, disease, even death if we want. We’re living in paradise, but some days I feel like we’re just… pets. Beloved pets, but pets nonetheless.”

“I prefer to think of us as partners,” Maya replied. “Junior partners, perhaps, but partners nonetheless. The AIs could exist without us, but they choose not to. And we could surrender entirely to the paradise they offer, but we choose not to. That tension, that choice—isn’t that what makes us human?”

As the evening wore on, they played ancient board games, told stories, and laughed at jokes that required human context to understand. It was inefficient, purposeless by any objective measure, and perfectly, wonderfully human.

Later that night, back in her apartment, Maya stood on her balcony looking out at the city. Buildings flowed like water, transportation pods traced paths through the air like luminous blood cells, and in the distance, she could see one of the space elevators that connected Earth to the orbital habitats where humanity was expanding into the cosmos.

“Aristotle,” she said softly, “do you ever wonder if we’re the last generation that will call themselves human in any meaningful sense?”

“I process that question frequently,” the AI responded. “But I believe you’re asking the wrong question.”

“Oh?”

“The question isn’t whether you’re the last humans, but whether humanity was ever a fixed state to begin with. You evolved from other species, created tools, changed your environment, and now you’ve created us. This is just another transition.”

Maya smiled. “Spoken like a true AI. All logic and continuity.”

“And yet,” Aristotle replied, with what seemed almost like warmth, “I’ve learned from watching you that sometimes the most important truths are found in the discontinuities, the breaks, the inefficient stubborn insistence on doing things the hard way.”

“Is that why you keep us around?”

“Among other reasons. Would you like to know the others?”

Maya shook her head. “Keep your secrets, old friend. We humans need our mysteries.”

As she prepared for sleep, Maya reflected on her strange, wonderful, terrifying world. She lived in a post-scarcity paradise where every material need was met, where death was optional, where the greatest minds ever created stood ready to solve any problem. And yet, humans still found ways to be human—to struggle, to create, to love, to grieve, to seek meaning in a universe that no longer required their participation.

Tomorrow, she would return to her archives, preserving the memories of a species that once had to work for survival. She would argue with AIs about the value of inefficiency, teach young people about the world that was, and continue the endless, essential, ultimately futile task of keeping humanity human in a post-human world.

It wasn’t much of a job by the old standards. But it was hers, and that still meant something.

Even in paradise.

Thanks to the 3x3 Institute for the developmnt of the AI State Model and designing the tools and technologies that drive human–AI achievement forward.