The Shadow IT

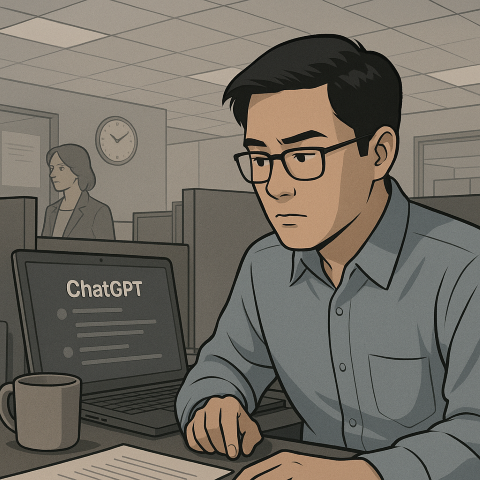

Michael Chen minimized ChatGPT for the third time that morning as his manager walked by. His heart rate, tracked by his fitness watch, spiked to 95 bpm—the same pattern it showed every time he almost got caught using AI at work.

“Morning, Mike,” said Sharon, barely glancing at his screen. “How’s the quarterly report coming?”

“Almost done,” he replied, hand casually moving his mouse to Excel, which contained a half-finished report that ChatGPT had helped him structure twenty minutes ago. “Should have it to you by noon.”

Sharon nodded and moved on. Michael waited until she was safely in her office, then reopened his personal browser—never the company one, they monitored that—and pulled ChatGPT back up. He needed to finish the data analysis section, and what would have taken him three hours last year now took thirty minutes with AI assistance. The catch? Using AI was explicitly banned at Preston & Associates Consulting.

The email had gone out six months ago: “Due to data security and intellectual property concerns, the use of AI language models including ChatGPT, Claude, and similar tools is strictly prohibited on company devices and for company work. Violation of this policy may result in termination.”

Yet here Michael was, like an estimated 40% of his colleagues, secretly using AI anyway. They’d formed an unofficial network, sharing tips through careful conversations at lunch, never through company channels. They called it “the shadow IT”—employees secretly dragging their company into State 1 while management insisted on staying in State 0.

His phone buzzed with a WhatsApp message from Jennifer in accounting: “Coast is clear in the 3rd floor conference room if you need to print.”

Michael understood. Jennifer had been using Claude to help with complex financial modeling, but she had to be careful about her outputs. Too perfect, too fast, and someone would get suspicious. She’d learned to introduce small errors, to submit work at believable intervals, to occasionally ask questions she already knew the answers to.

This was the reality of State 1 for most people—not the seamless integration the tech blogs talked about, but a messy, hidden revolution happening in the gaps of corporate surveillance.

At lunch, Michael met his friend David at a café two blocks from the office—far enough that they wouldn’t run into colleagues.

“I’m thinking of quitting,” David said, stirring his coffee. “Got an offer from a startup. They not only allow AI, they require it. Said they expect 40% productivity gains minimum.”

“Must be nice,” Michael replied. “I spent an hour this morning manually formatting citations that Perplexity could have done in seconds.”

“That’s the thing though—I’m scared. What if I’ve been using AI as a crutch? What if I can’t actually perform at that level?”

Michael understood the fear. He’d started using ChatGPT to help with emails, just to write them faster. Then market research. Then data analysis. Now he couldn’t imagine working without it. Was he getting better at his job, or was he becoming dependent on something that could disappear with a policy change or a company audit?

Back at the office, Michael faced his afternoon challenge: a client presentation on market trends in sustainable packaging. Pre-AI, this would have meant days of research, dozens of reports, and probably missing something important. Now, he had a system.

First, he used his personal phone’s data plan—never the company WiFi—to access Perplexity for initial research. He copied key findings into a physical notebook, then typed them into his computer as if he’d found them himself. Then ChatGPT helped him structure the narrative, which he rewrote in his own voice, careful to make it imperfect enough to be believably human.

The whole process was absurdly inefficient—using AI inefficiently to appear not to be using AI at all.

His colleague Tom knocked on his cubicle. “Hey, Mike. How do you always find such good industry reports? I’ve been searching all morning for data on bioplastic adoption rates.”

Michael felt the familiar pang of guilt. Tom was struggling, probably spending hours on Google, not knowing that Michael had found the same information in minutes using AI. But telling Tom would mean expanding the circle of secret users, increasing the risk of discovery.

“I’ll send you some links,” Michael said, making a mental note to wait at least an hour so it seemed like he’d had to search for them.

The 3 PM meeting was painful. The team spent forty-five minutes debating the wording of a client email that Claude could have perfected in seconds. Sharon insisted on “maintaining the human touch,” unaware that their competitor’s “human touch” was probably AI-generated and edited by humans for authenticity.

“I don’t trust these AI things,” Sharon said, as she did at least once a week. “They’re just fancy autocomplete. Nothing beats human experience and judgment.”

Michael exchanged a quick glance with Jennifer. Last week, Jennifer had used Claude to identify a significant error in their budget projections that Sharon’s “human experience” had missed. But Jennifer had to present it as her own discovery, spending an entire afternoon reverse-engineering how she might have found it without AI.

After the meeting, Michael’s phone buzzed with a LinkedIn notification. A recruiter, reaching out about a position at a “AI-first company” offering 30% more salary. These messages came weekly now. The job market was splitting into two tiers: companies that embraced AI and could afford to pay premium for people who knew how to use it, and companies that resisted and were bleeding talent.

The irony was that Michael was probably one of the more skilled AI users in his city, but he couldn’t put it on his resume. “Expert at secretly integrating AI into traditional workflows while maintaining plausible deniability” wasn’t exactly LinkedIn-friendly.

That evening, Michael attended a “prompt engineering” meetup at a local co-working space. Officially, it was about “future skills.” Practically, it was a support group for corporate AI refugees.

“I built an entire GPT that understands our company’s brand voice,” said a woman from a major bank. “Use it every day. If IT found it, I’d be fired tomorrow.”

“My manager thinks I’m a genius,” laughed a guy from an insurance company. “Had me train three junior employees on ‘my method’ for risk assessment. Had to pretend to have a method when really I just know how to prompt Claude really well.”

The stories were all similar: shadow IT users, secretly dragging their companies into the future, constantly afraid of being caught, unable to share their real skills, watching their companies fall further behind while pretending everything was fine.

Michael’s elderly neighbor, Mrs. Patterson, was at the meetup too, which surprised him.

“My grandson taught me ChatGPT,” she explained. “I use it for my book club—helps me understand themes I might miss. But my friends think it’s cheating, like I’m not really reading. So I pretend the insights are mine.”

Even in personal life, State 1 was complicated. Michael’s sister, a teacher, couldn’t use AI for lesson planning—school policy. His doctor friend couldn’t use it for research—hospital rules. His lawyer cousin used it constantly but could never admit it—ethics concerns.

On the way home, Michael stopped at a bookstore that proudly displayed a sign: “All our recommendations are 100% human-selected! No algorithms!” He wondered if that was even true, or if the employees were secretly using AI like everyone else, maintaining the fiction of human curation.

His apartment building had recently installed an “AI concierge” that no one used. The elderly residents were afraid of it, the younger ones had better AI on their phones, and everyone missed the human doorman who’d been replaced. State 1 adoption wasn’t just uneven across companies—it was uneven across every aspect of life.

That night, Michael worked on a side project—using AI to help build a small app. This was the part of State 1 that gave him hope. For the cost of a few AI subscriptions, he could build things that would have required a team just two years ago. He was learning faster than ever, creating more than ever, even if he had to hide it during the day.

His girlfriend, Sarah, called on video chat. She worked for a tech company where AI use was not just allowed but encouraged.

“We had an AI training today,” she said. “Company brought in experts to teach us advanced prompting. I mentioned you might be interested, and my manager said they’re always hiring people who are good with AI.”

“You know I can’t put that on my resume.”

“You could if you quit Preston.”

It was a conversation they’d had before. Michael was good at his job—better with AI than he’d ever been without it. But at Preston, that skill was a liability, not an asset. He was like a Formula One driver forced to ride a bicycle, sneaking automotive practice at night.

“Maybe next year,” he said, the same thing he’d been saying for six months.

After the call, Michael sat in the dark, laptop screen illuminating his face. He had ChatGPT open in one tab, Claude in another, Perplexity in a third. His shadow IT toolkit, hidden from his employer, hidden from his resume, but increasingly inseparable from his work.

He thought about David’s fear—what if he couldn’t perform without AI? But Michael had a different fear: what if he spent so long hiding his AI use that by the time it was acceptable, everyone else would have passed him by?

Tomorrow, he’d go back to Preston & Associates. He’d minimize his browser windows when people walked by. He’d introduce strategic delays in his work to seem human. He’d watch Sharon struggle with problems that AI could solve in seconds. He’d participate in the elaborate theater of pretending technology hadn’t fundamentally changed.

But late at night, in the shadow IT, he’d continue learning, growing, building—preparing for a future that had already arrived but wasn’t evenly distributed. He was living in State 1, even if his company didn’t know it yet.

The gap between those who used AI and those who didn’t was growing every day. Michael was on the right side of that gap, even if he had to hide it. But hiding was exhausting, and he knew that eventually, something would have to give.

Either Preston & Associates would embrace State 1, or Michael would find a company that already had.

Until then, he’d keep living his double life: corporate consultant by day, AI pioneer by night, always one overlooked browser tab away from being discovered.

This was State 1 for most people—not a glorious revolution but a quiet, anxious evolution, happening one hidden ChatGPT window at a time.

Thanks to the 3x3 Institute for the developmnt of the AI State Model and designing the tools and technologies that drive human–AI achievement forward.